The last time I saw Iranian artist Sadegh Tirafkan was in the fall of 2011 at Art Abu Dhabi. Sadegh was there to soak it all in and to attend an opening of his art at Etemad Gallery in Dubai. As I stood in line to board a bus to dinner for invited participants, he enveloped me in a hug and said, “Eh, Shiva jan, I have a project I want to talk with you about.” We sat together on the bus, chatting and watching Abu Dhabi pass by.

Sadegh wanted us to travel to Iran together. We would drive around the country, visiting its faraway villages and its crowded cities. We would climb its mountains and sit alongside its seas. We would tour its museums and historic sights. He would take photographs and I would write. And then we would turn it all into a beautiful book.

My eyes brimmed with tears as I looked at him, all passion and determination. “Sadegh jan,” I replied softly, “if only we lived in a world where it was possible for you and me to travel and work together like this in Iran.” He looked puzzled, bowed his head down in recognition, and then insisted, “We’ll do it someday. Yek ruz.”

As we got off the bus, we merged into a reception line to greet the Crown Prince and his family who were hosting the dinner. Sadegh disappeared into the crowd. I found myself standing beside Tony Shafrazi and spent the rest of the night listening to him reminisce about the Tehran art scene in the 1970s. Among the things Abu Dhabi has become is a place where Iranians who make art, exhibit art, collect art, sell art, and write about art can gather. Abu Dhabi accepts all of our passports so long as we have art and commentary to offer.

The first time I met Sadegh was in New York in the late 1990s. Peter Chelkowski, my colleague at New York University, and I were trying to convince the Grey Art Gallery to organize an exhibit of Iranian art. (The show “Between Word and Image” and the book Picturing Iran: Art, Society and Revolution were the fruits of those original schemes.) Peter invited me to go to a private gallery on the Upper East Side to see the work of a young photographer. We spent a few hours drinking tea and chatting with Sadegh.

Like my paternal grandmother, Sadegh was born in Iraq to a religious family. His family moved from Karbala to Tehran when he was five. He lived through the revolution as a teenager. During the Iran-Iraq war, he served as a basij for three years. After the war, he studied photojournalism. His own style of art making—mixed media work, video art—was something he learned through experimentation, from absorbing others’ work, and from what he observed around him.

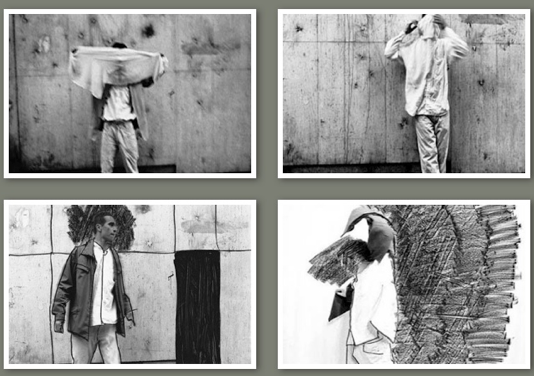

In 2001, Sadegh held his first conceptual art exhibition at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, showing works from his “Ashura” series. He appears in these photographs as well, signaling how personal the exploration of Shi’i rituals is for him. “I often put myself in my photographs,” he told me. “I’m like a storyteller, like a playwright staging a scene. I participate in these rituals; they are part of my system of belief going back to my childhood. For me, it’s more a question of nostalgia, of childhood memories.”

The self-referential aspect of his photography also points to the question of identity—his own and his generation’s. Speaking at the Asia Society in 2004, he explained: “As an Iranian living in the year 2000 who has experienced the revolution and the war, what have I seen? And what did other Iranians in the past experience? Being Iranian is very important to me.”

When he visited New York, Sadegh and I would sit for long talks and he would show me his most recent work. When he was in Canada or Tehran, we would speak over the phone or communicate by email. The last time we communicated, I was preparing to speak about his art as part of my lecture on masculinity in Iranian art at the Los Angeles Contemporary Museum of Art last December. LACMA, he reminded me proudly, was among the first international museums to exhibit and collect his work.

Sadegh liked to talk. But he never told me he was sick, never told me he was dying. The only thing we ever talked about was art—why he made art, how he made art, where he wanted to take his art. Sadegh was always searching for a new way to make art, a new understanding of himself, a place he felt at home. I always thought this is why Shirin Neshat’s art was so compelling to him. Some have noted that his work echoes hers. Listening to Sadegh, I felt that the mimetic urge came from a desire to find his own home in his art, the way she has. When the earth shakes and you have no ground to stand on, you have to create your own home. Shirin’s artistic oeuvre is a beautiful manifestation of that impulse.

Sadegh was still searching for that place that was his home, where he could live in peace in his own skin. And I understood that impulse. Maybe that is why he wanted us to journey through Iran, searching for that place together.

Sadegh began making black and white photographs around the same time Shirin was making her "Women of Allah” series. Sadegh’s “The Empty Walls in Tehran” (1994-96) are achingly beautiful images of himself against the city’s gray walls. Finally, he begins to draw on the images, searching to make something, to find someplace. “Tehran,” he explained, “a city with ten million inhabitants, is my home and a constant preoccupation... In this polluted and busy city human beings are lost and it seems that they have no control over their destinies. They build walls around themselves without being aware of them. One can see many people passing by these walls every minute. But I can see only walls with no human beings in front of them.”

As I was sipping my morning coffee one May morning, I checked my Facebook. An Iranian artist had written a status update that read simply, “Sadegh.” What has happened to Sadegh? I rang the artist Nicky Nodjoumi in Brooklyn. He told me Sadegh had died of brain cancer. And before he passed, he had asked to speak with Shirin Neshat, even though he was already too far gone to have a proper conversation. It makes sense to me that he would want to hear her voice one last time.

Ever since that morning, I have had a picture of Sadegh on my computer. It is a reminder to honor his life and work by writing about him. But the picture of a young gifted artist with sad eyes has made it even harder to eulogize him. Death is one of exile’s greatest difficulties. Exile is like a shadow that follows you wherever you go, but engulfs you when someone dies. As long as there is life, there is that hope of return. As friends and family die, as they are buried in strange lands, exile seems permanent, incurable. Exile itself begins to feel like a kind of death.

Sadegh Tirafkan died too young, in too painful a way. But before he left, he had found recognition. I heard he also had found love, and I hope he had found his home. In the end, for us all that remains is his art.

![[Sadegh Tirafkan self-portrait from his Ashura Series, 1997 - 2008.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Tirafkan.AshuraSeries(1997-2008).png)